A quick primer on early 19th century romance through the example of two bachelors. Both stubborn, passionate, and persevering towards the objects of their affection. However, one seemed to garner greater success in his relationships than the other. What sets them apart?

First, an introduction:

Mr C

The first, a Congregationalist minister seeks a bride in the early 19th century. Unfortunately, the letters to his objects of desire have not survived (or not yet been found) but we can garner a few insights into his behaviour from the letters of one particular lady whose name was, rather appropriately, Elizabeth Bennett. Elizabeth’s first letter of response to Mr C’s approach reveals her surprise. Her response gives the impression that she is befuddled by his letters to her. She indicates that she had not even given a slight thought to him as being a potential husband for her, and she declines his proposal –

Elizabeth also tries to, very kindly, let down Mr C with a 19th century version of ‘it’s not you – it’s me’ with the following explanation –

“I am, you know, bereft of affectionate parents, whose knowledge of human life, added to their solicitude for my welfare, would have relieved me from the painful anxiety of acting for myself.’

Elizabeth platonically begins and concludes this letter in such a way which gives no doubt – ‘Dear Sir’ and ‘Yours, very respectfully, Elizabeth Bennett’

However, Mr C did not let this small impediment delay his cause. Another letter from Elizabeth one month later indicates that he had continued in his ‘solicitations’ of her hand in marriage. Elizabeth, in another platonically saturated letter, once again refuses his offer. This time she makes it crystal clear – “I am induced to confess that I cannot feel that affection for you which is so essentially necessary…to such an important union.”

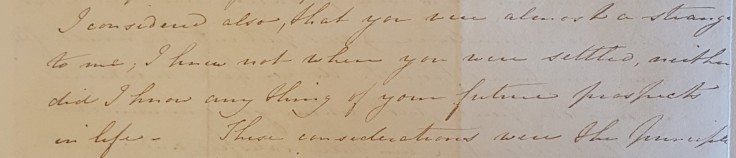

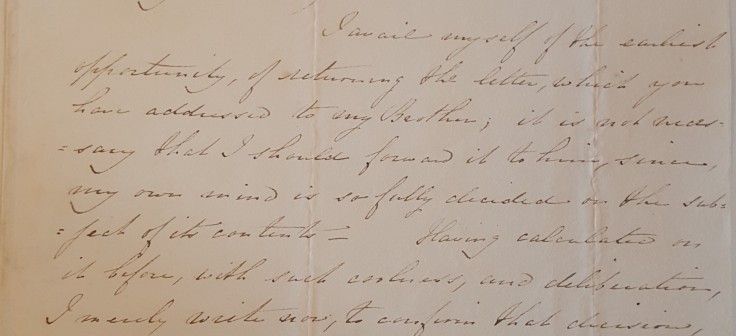

Mr C still persevered, as is evident by the third and final letter we have addressed to him from Elizabeth. In this letter, the least amicable of her collection, Elizabeth requests that Mr C does not contact her again – directly or otherwise. On this occasion, Mr C had written a letter to her brother, which, as indicated by Elizabeth, was another appeal for her hand in marriage. This is Elizabeth’s response:

Mr Q

Our second bachelor example was a Quaker tea merchant (Mr Q) whose perseverance in pursuing a young Quaker lady from a wealthy banking family concluded quite happily for him, unlike Congregationalist Mr C.

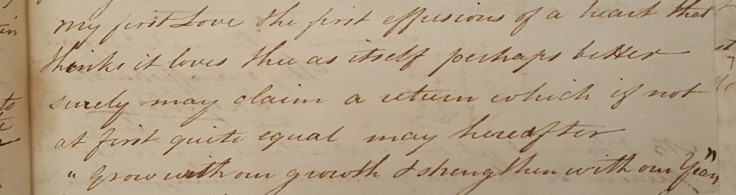

The correspondence about potential marriage begins in early 1800, after Mr Q exchanged a plethora of letters with our lady’s father receiving advice, friendship, and requesting his daughter’s hand in marriage. His intentions become apparent to the future Mrs Q at a visit early in 1800. His first letter to her is long, passionate, and filled with affection. He concedes that she may not yet feel as deeply for him as he does for her, as she expressed these concerns when they took a walk around the gardens during his last visit. However, he expresses appreciation for this honesty:

“Tho it could but be painful to hear even the doubts of adequate attachment thou expressed thou said it relieved thy own mind and if so, so far I ought to be satisfied.”

He contends that if she accepts his proposal, her love, though not equal with his initially might grow in time: “[your love may] grow with our growth and strengthen with our years”

Within six months the lady has been convinced to marry Mr Q, and they are to wed in their meeting-house.

What’s the difference?

Wherein lies the difference between these two bachelors? Why did perseverance succeed for the latter and fail for the former? Might it simply be the case that the former lady was stubborn and refused to consider her friend as a possible mate, or was there something deeper at the ‘heart’ of this difference.

Though, as mentioned, we do not currently have surviving letters from Mr C to Elizabeth – we do have some letters to the lady who does succumb to his pursuits – his wife Sarah. In these letters, Mr C expresses particular attitudes and temperament which may explain the unfavourable outcome of his earlier pursuits.

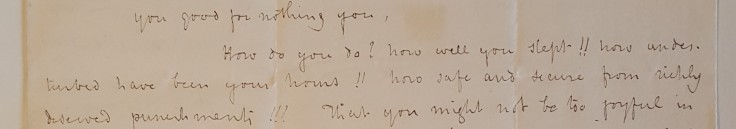

In one of the earliest letters to his wife, Mr C addressee his letter to his dearly beloved as follows:

And what prompted this curt address to his new wife? Mr C goes on in the letter to scold his wife, quite aggressively, for her absence during his latest preaching engagement. A few members at the chapel asked why his wife had not accompanied him, and he makes it clear that this caused him profound embarrassment. He suggests to Sarah that he is a kind and loving husband, as he did not tell them she was at home in bed, enjoying undisturbed slumber.

“…I did not say [to them] how you were burdened with sin, see how kind and tender I behave towards you…”

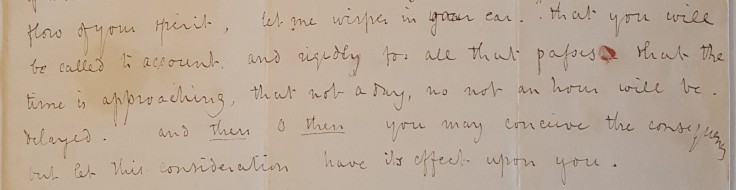

He suggests that the Lord will deal with her for not supporting her husband:

Later in this same letter Mr C once again scolds his wife for not responding to his letters promptly After narrating the ‘news’ of his latest travels, he implores his wife to send him the news of her days.

“I shall expect a letter [from you] Monday morning…full of obedience and affection.”

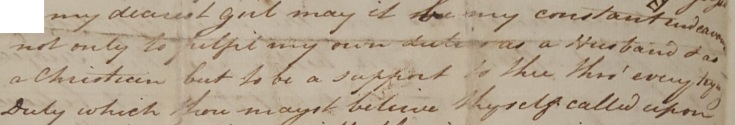

This is a stark contrast to the way that Mr Q behaves towards his desired lady. While Mr C demanded Mrs C to be an obedient and submissive wife who supports his ministry, Mr Q makes it clear to his future wife that they would be partners in their ministerial work together. In the first letter to his future wife mentioned above, Mr Q closes the letter by arguing the following:

While both men were passionate towards their significant others, it is little wonder that Mr Q was so readily received by his future wife, while Mr C had to endure a few rejections first.

And a little application for our day: Men – be like Mr Q, not like Mr C.

Thank you for sharing these amazing letters. And hurrah to Elizabeth for standing her ground!

LikeLike