On the 6th of April 1842 the Police Constable, William Gardner, was on duty in Wandsworth, when a tradesperson, Mr Collingbourn, approached him with a complaint. Local man, Daniel Good had stolen a pair of black trousers from his shop and he wished to press charges. Good was the coachman for Mr Shiell, in Putney, Park-lane – and thus that became Gardner’s next stop. After being directed by Mr Shiell to the stables, where Good resided, Gardner, and two officers who had accompanied him – Speed and Dagnal – approached Good and indormed him that they had been sent to take him into custody on charges of theft of black trousers from Mr Collingbourn’s store. Good responded casually, neither admitting guilt for this crime nor denying his possession of the said trousers. “Yes, I bought a pair of breeches of Mr. Collingbourn, and I did not pay him for them.” Good offered to give the money to Gardner, suggesting “You can take the money to him”

Gardner refused this arrangement – he was not a courier, his business was to arrest Good for the charge of theft, not settle the matter for him. PC Gardner, with a subtle twinge of annoyance replied, “No, that has nothing to do with the charge I have come upon.” Good then conceded to coming with the officers to Wandsworth, in order to settle the matter directly with Collingbourn. Gardner’s next decision significantly altered this investigation, quickly propelling it into a much more serious incident than theft. Indeed, it was likely to become the most memorable crime Gardner would investigate throughout his whole career.

Gardner refused this arrangement – he was not a courier, his business was to arrest Good for the charge of theft, not settle the matter for him. PC Gardner, with a subtle twinge of annoyance replied, “No, that has nothing to do with the charge I have come upon.” Good then conceded to coming with the officers to Wandsworth, in order to settle the matter directly with Collingbourn. Gardner’s next decision significantly altered this investigation, quickly propelling it into a much more serious incident than theft. Indeed, it was likely to become the most memorable crime Gardner would investigate throughout his whole career.

We don’t know why Gardner decided to embark upon further investigation, even after Good conceded to accompany them to the station in Wandsworth. Perhaps Gardner was suddenly beset with a “gut-feeling” type intuition which told him there was more to this story. Or, maybe he was feeling perturbed at Good’s response to Gardner’s arrest and wished to cause him further inconvenience. Sadly, the notes on the case do not offer an answer.

What happened next was this: Gardner asked whether Good would consent to himself and his officers searching the chaise and stable – in order to apprehend the trousers. Good, without a hint of concern, granted permission. Gardner walked with his two officers to the stable-yard, preparing to enter the stable and search for the trousers.

Gardner asked the more senior officer of the two, Speed, to stay with “the prisoner” while he conducted a search of the area. As he headed to the stable to begin his search, Good blocked the door and suggested that they head to Wandsworth to settle the matter, without delay. Gardner, now feeling significantly suspicious of the situation, told Good that he would not be leaving until he had conducted a thorough search of the stable. Good consented, again, and Gardner began to investigate. He searched the first and second stalls, discovering nothing untoward – and no trousers. Before he entered the third stall, Good swiftly slid into the fourth stall and moved a truss of hay. Gardner, whose suspicions must have been on high alert by this time (or – perhaps he just thought Good an extremely odd fellow?) – decided it would be sensible to search this particular stall next. After the prisoner had been returned to the officer who meant to be guarding him (who already seemed to be doing a rather poorly job, we must note), Gardner headed into the fourth stall.

He moved the truss of hay which Good had just shifted – but nothing seemed amiss. He considered whether more sleuthing was necessary – several trusses of hay were stacked in the stall, after all. He noticed some loose hay underneath, and something which, to Gardner, resembled a dead goose. Gardner, then decided to question “the prisoner” about this strange discovery. “What is this? This is a goose.” he said loudly, for all in the stable to hear. At that moment, to the dismay of all three officers, Speed demonstrated once again, his lack of control over his prisoner (and, indeed, unsuitability to carry his name-sake). Good, with much speed of his own, had slipped out of the stable, slammed the door shot, and locked the three officers inside. Speed attempted to open the door with a pitch-fork he found in the stable, while Gardner continued to examine the goose. He moved off the rest of the bits of hay, and discovered it wasn’t a goose – it was a pig! Well, mystery solved!

Gardner decided to move a bit more of the hay off, and discovered that this shocking discovery was neither goose nor pig – but the trunk of a female body. The arms were missing – cut off at the shoulder, as were the legs – cut off at the thigh. The head had been removed at the lower neck, and the belly was cut wide open with innards spilling out (clearly – it is easy to understand why such a sight might be mistaken for a goose or pig, given the resemblance…)

Gardner decided to move a bit more of the hay off, and discovered that this shocking discovery was neither goose nor pig – but the trunk of a female body. The arms were missing – cut off at the shoulder, as were the legs – cut off at the thigh. The head had been removed at the lower neck, and the belly was cut wide open with innards spilling out (clearly – it is easy to understand why such a sight might be mistaken for a goose or pig, given the resemblance…)

At any rate, what was clear was that Gardner had stumbled upon a murder. The case of the black stolen trousers had turned into one of a heinous murder.

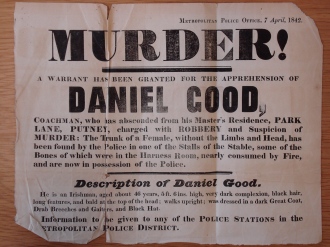

When Gardner and his fellow officers finally made their way out of their predicament, they gave chase to Good – off to catch this murderous fiend. But, first they had to make a pit stop at their headquarters. Unfortunately, this was the proper procedure in such a case – and – despite the fact that Good had a head start, was in all probability a dangerous murderer – bureaucracy still won the day. Gardner compiled notes the events as they had occurred, and updated his superiors. After presenting these to his superiors, he sent route papers to nearby districts with information about Good. Before telephones and radios, route papers were the traditional way to send details of criminals at large to neighbouring districts. Upon their receipt, each division chief would initialise the form, indicating they had received this information. Unfortunately, they were frequently not fast enough. Indeed, this was the case for Good, for he remained a few steps ahead of the officers and continued to evade capture. His eventual arrest was successful when a retired police officer living in Tonbridge recognised him and immediately apprehended him. Good was arrested, and put to trial, for the murder of his common law wife, Jane Good.

Jane had moved to Manchester Square about three years ago, and took lodgings with the wife of John Brown. Ms Brown was able to shed some light on their relationship history. Apparently Good had taken it upon himself to frequently visit Jane; it was unclear why he came around to visit Jane, though Jane always said he was just a friend. After Good’s wife died, he began calling Jane his wife, and his young child called Jane his mother. On the 3rd of April, Jane left her lodging house, telling a friend she was going down to visit Mr Good. A confectioner in Putney later recounted seeing Good with a female walking arm-in-arm – whom he introduced to her as his sister. It is unknown whether this woman was Jane – or another young lady. What is known, is that after 3 April, Jane was never seen again.

Jane had moved to Manchester Square about three years ago, and took lodgings with the wife of John Brown. Ms Brown was able to shed some light on their relationship history. Apparently Good had taken it upon himself to frequently visit Jane; it was unclear why he came around to visit Jane, though Jane always said he was just a friend. After Good’s wife died, he began calling Jane his wife, and his young child called Jane his mother. On the 3rd of April, Jane left her lodging house, telling a friend she was going down to visit Mr Good. A confectioner in Putney later recounted seeing Good with a female walking arm-in-arm – whom he introduced to her as his sister. It is unknown whether this woman was Jane – or another young lady. What is known, is that after 3 April, Jane was never seen again.

This case elicited severe criticism from the press, attributing the issues in apprehending Good to the incompetency of the police. Furthermore, unnecessary bureaucratic rules gave Good further opportunity to evade capture. An article in The Times offered the following criticism, arguing that the bureaucracy was a ridiculous impediment to necessary police work:

“… Good could not have reached a distance of two miles from the spot. What was done towards accomplishing his recapture? Did the constable go in pursuit of him? No; he would not have been justified in doing so without the orders of his superior officer…”

The verdict of the court was guilty, and Good was, unsurprisingly, summarily executed for his heinous crime. It is additionally unsurprising to find that the case of Daniel Good was one of the incidents which catalysed the foundation of the new detective branch of the police force, implemented in 1842.

Leave a comment